Olympic Lifting for Stronger Bones

Introduction

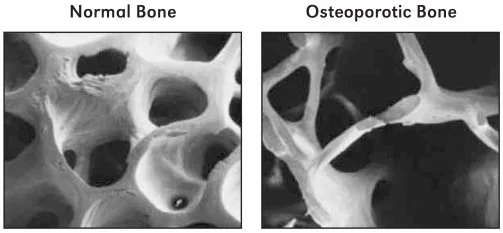

Osteoporosis is a major concern for the aging population. It is a condition where someone has a pathologically low level of bone density, increasing the risk of fractures. These fractures are particularly problematic in the aging population, for whom rehabilitation can be difficult, and the potential time away of regular activity during said rehabilitation can lead to significant functional decline. It develops slowly as we age and often isn’t recognised until after fracture or injury occurs.

It is therefore even more important that we are already engaging in osteoporosis-preventative behaviours, rather than waiting until injury or diagnosis, by which time significant regression in bone mineral density may have already occurred. But how does one prevent, or even reverse, osteoporosis? Strength training. Lifting heavy weights is the gold standard conservative treatment for reducing the risk of osteoporosis.

What Type of Lifting is Best for Preventing Osteoporosis?

All lifting is good. But there is research suggesting that Olympic weightlifting has a greater effect on bone mineral density than other types of lifting, like powerlifting (Harrison, 2018). And what more, the better you are at weightlifting, the greater the association to higher bone density (Paillard et al., 2022). The hypothesis behind this being that the rate of loading associated with the fast-heavy lifting we see in Olympic Weightlifting is uniquely beneficial for increasing bone density. A nice way to think about training your musculoskeletal system is that the ‘harder the structure, the greater the intensity needed to affect it’. Bones are pretty hard, so to stress them (which is required to strengthen them), we need to load them with very high intensity. That being said, if you don’t enjoy Olympic weightlifting, you can still benefit greatly from powerlifting or other modes of lifting weight, but intensity is key.

What About Running to Reduce Osteoporosis?

Other common modes of recreational exercise, like running, are not so strongly associated with such high levels of bone density (Erickson et al., 2020); running is great for training your cardiorespiratory system, but not as good as lifting weights for protecting against osteoporosis (Erickson et al., 2020). So, if you enjoy running and wish to continue to run into middle and older age, without high risk of chronic musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries, like stress fractures, you should be engaging in regular heavy lifting too. Two sessions of heavy lifting a week, alongside your running, will suffice. This is in line with World Health Organisation Guidelines for weekly ‘muscle-strengthening sessions’ (Bull et al., 2020).

What Do You Need in Order to Learn Olympic Weightlifting?

1) Access to a barbell

2) Access to a coach/guide to follow

3) A desire to learn to Olympic weightlifting

That’s it. A good coach can progress or regress the lifts based on your needs. You do not need to be ‘good enough’ to start. You get ‘good enough’ by starting.

If you are interested in trying Olympic Weightlifting, but want help doing so, check out the OpenGym class schedule and get yourself booked in for a weightlifting session.

References:

1. Harrison, J.M., 2018. Olympic lifting is superior to power lifting in improving bone mineral density (Doctoral dissertation).

2. Paillard, T., El Hage, R., Al Rassy, N., Zouhal, H., Kaabi, S. and Passelergue, P., 2022. Effects of different levels of weightlifting training on bone mineral density in a group of adolescents. Journal of Clinical Densitometry, 25(4), pp.497-505.

3. Erickson, K.R., Grosicki, G.J., Mercado, M. and Riemann, B.L., 2020. Bone mineral density and muscle mass in masters olympic weightlifters and runners. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 28(5), pp.749-755.

4. Bull, F.C., Al-Ansari, S.S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M.P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.P., Chastin, S., Chou, R. and Dempsey, P.C., 2020. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British journal of sports medicine, 54(24), pp.1451-1462.

5. Office of the Surgeon General (US). Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2004. Figure 2-5, Normal vs. Osteoporotic Bone.